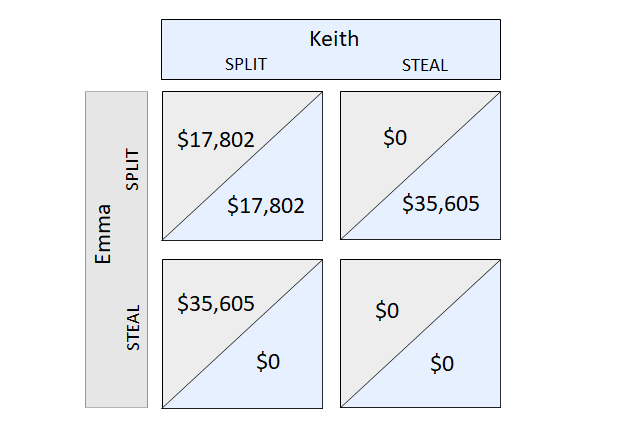

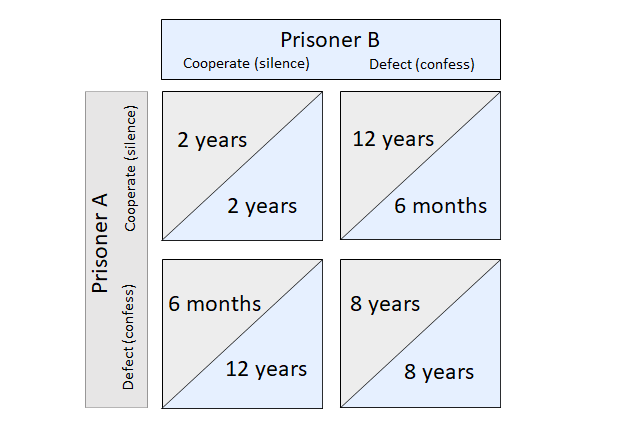

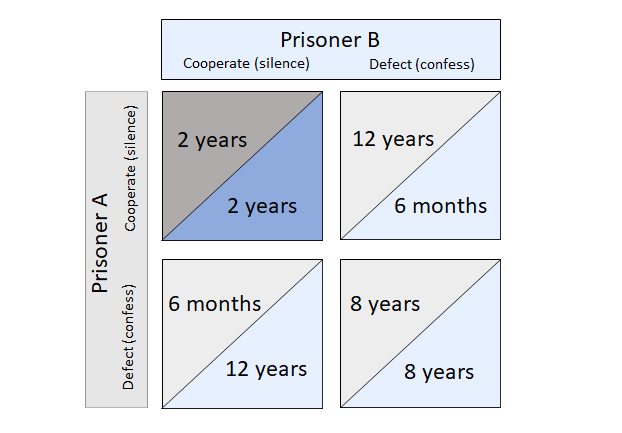

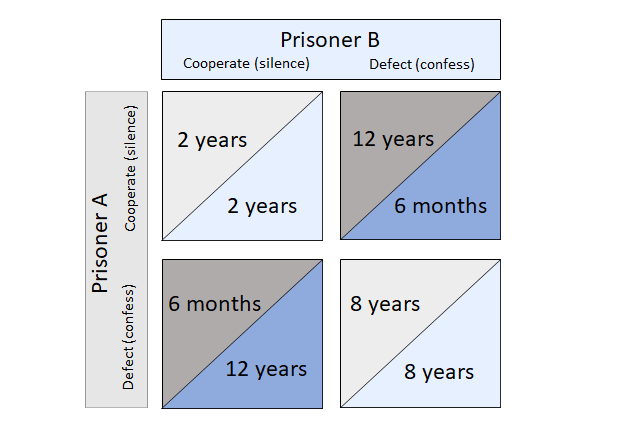

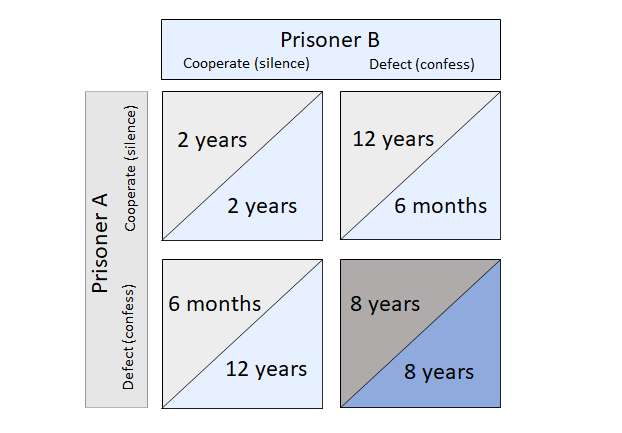

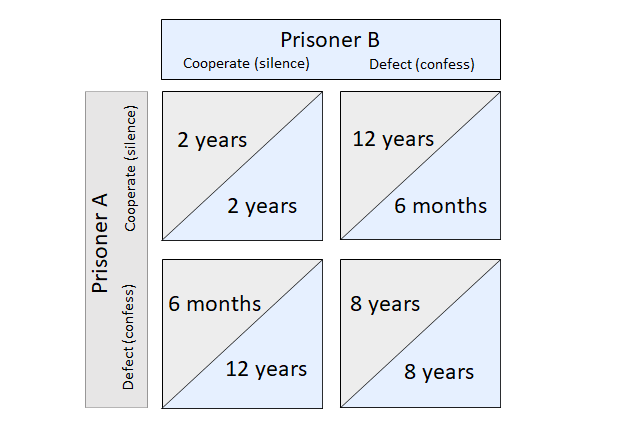

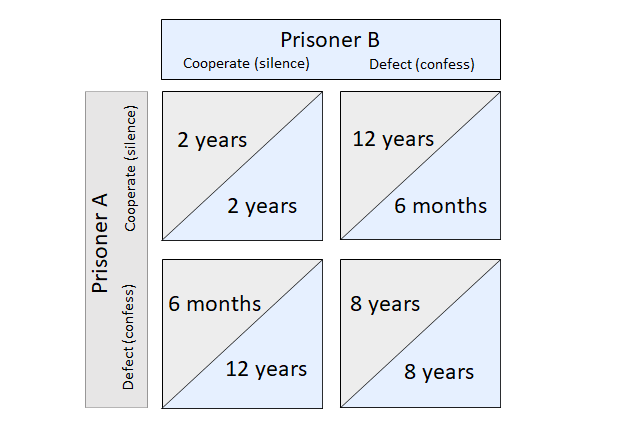

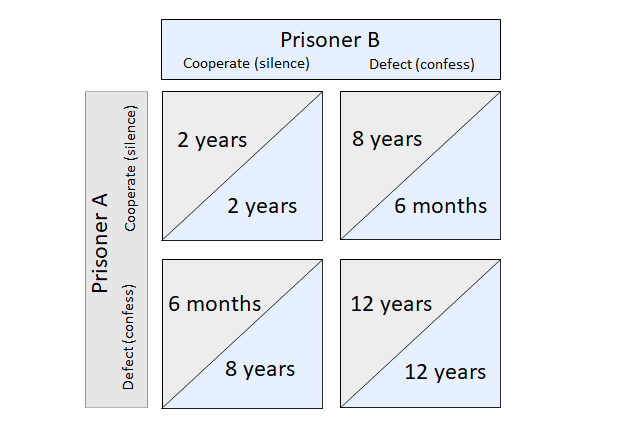

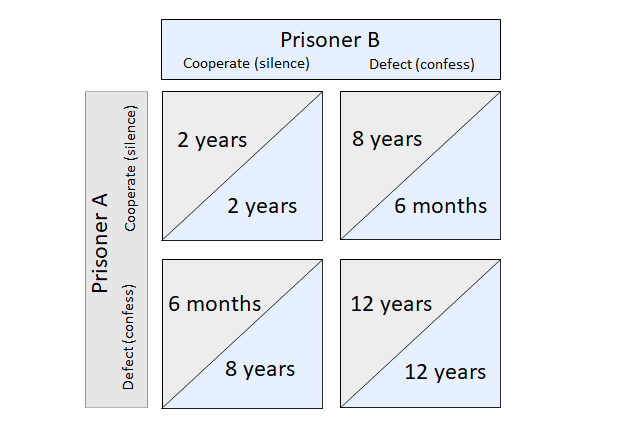

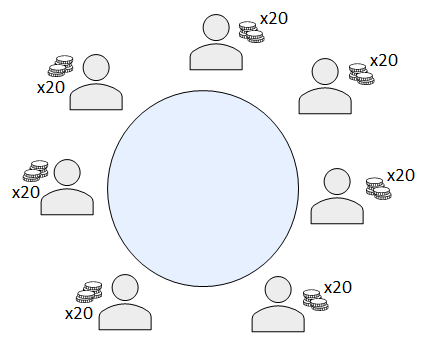

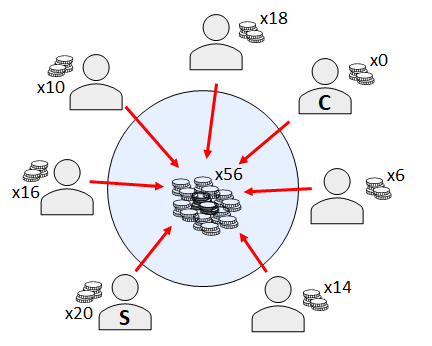

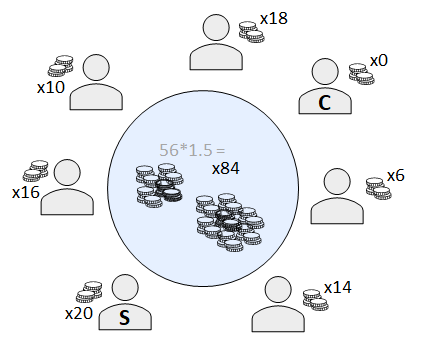

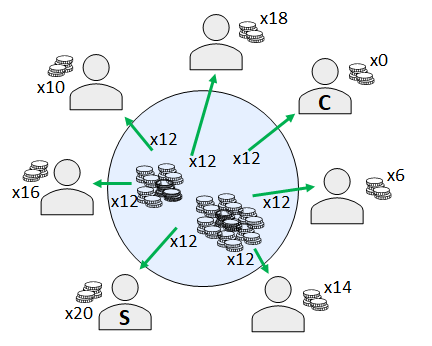

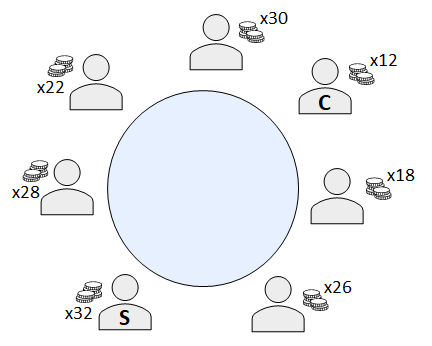

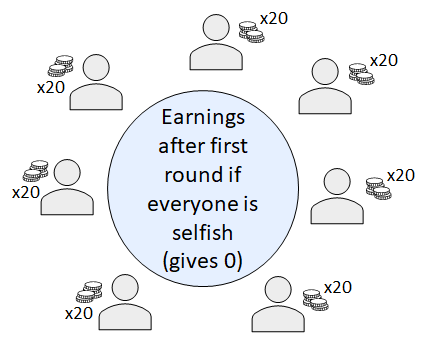

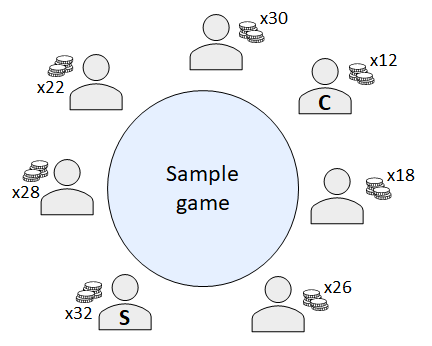

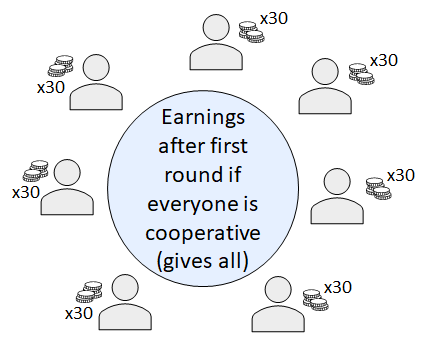

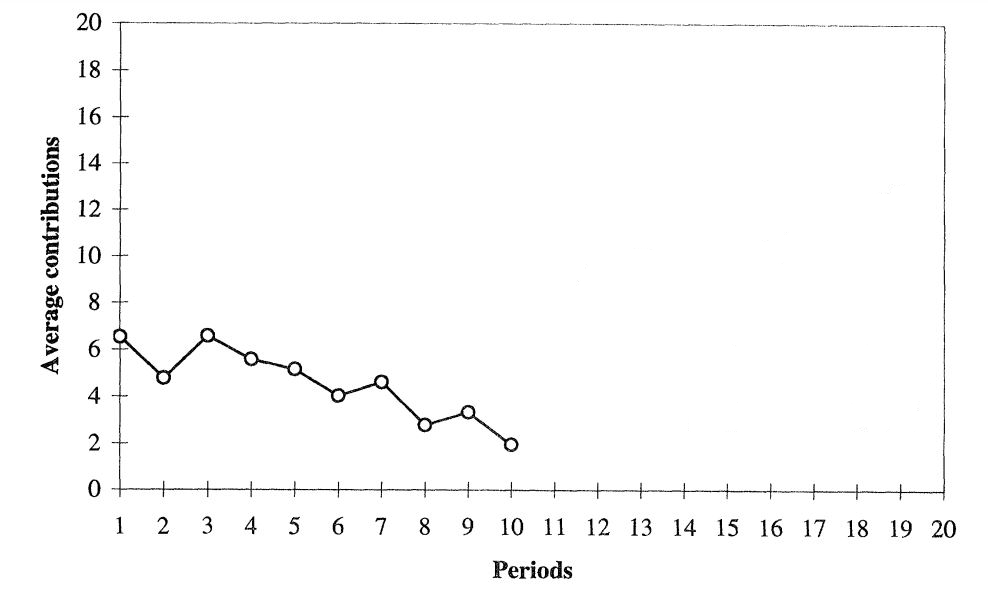

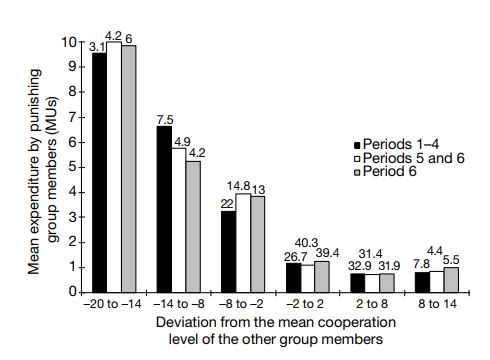

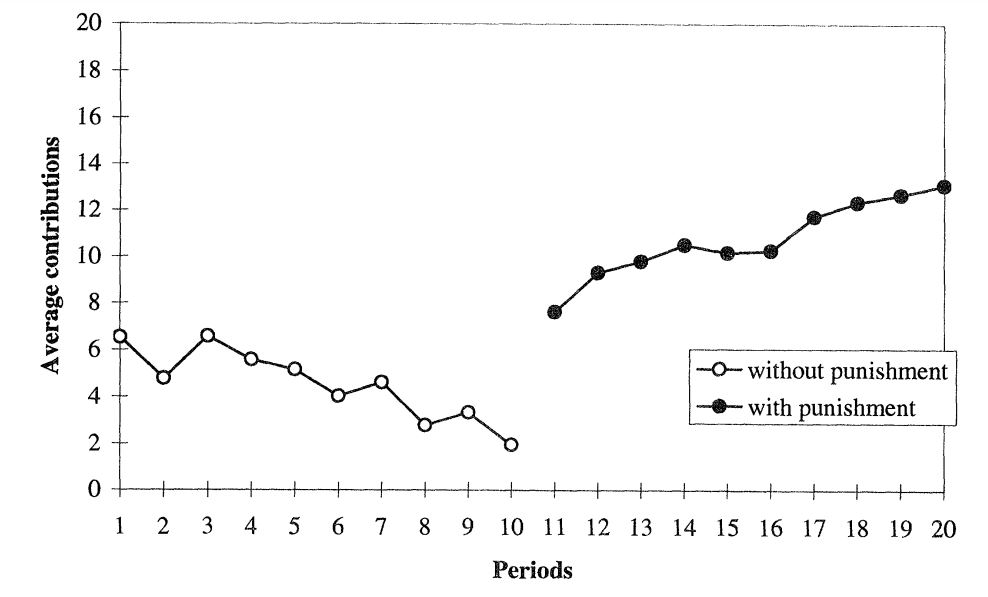

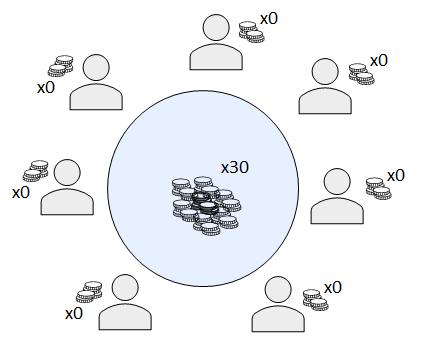

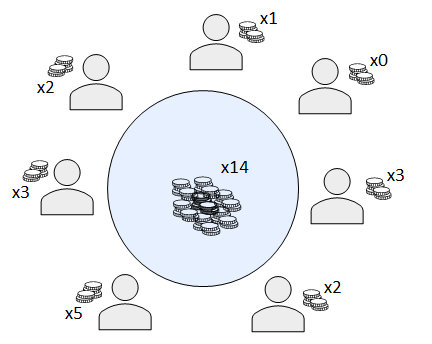

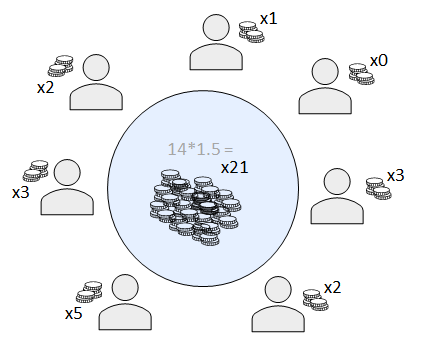

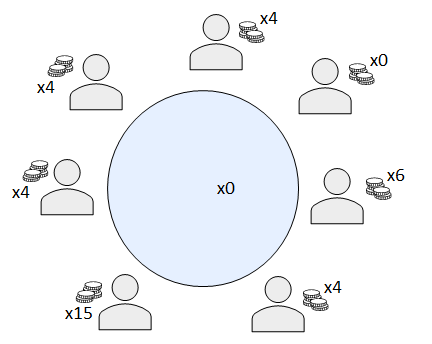

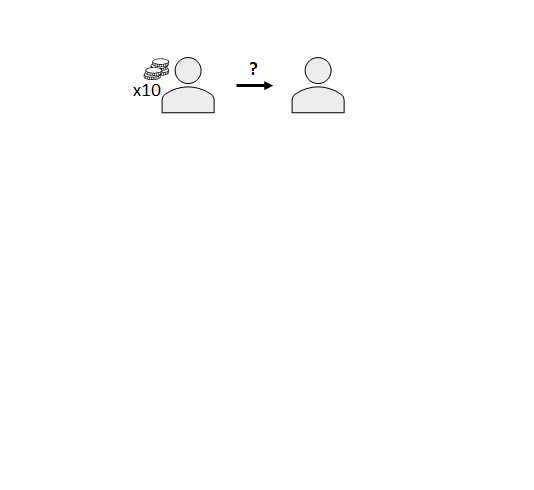

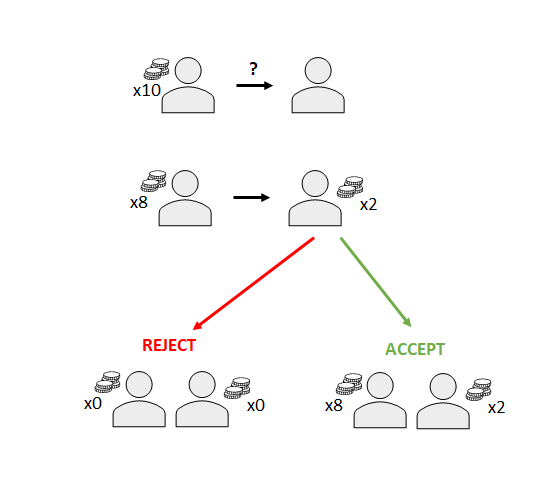

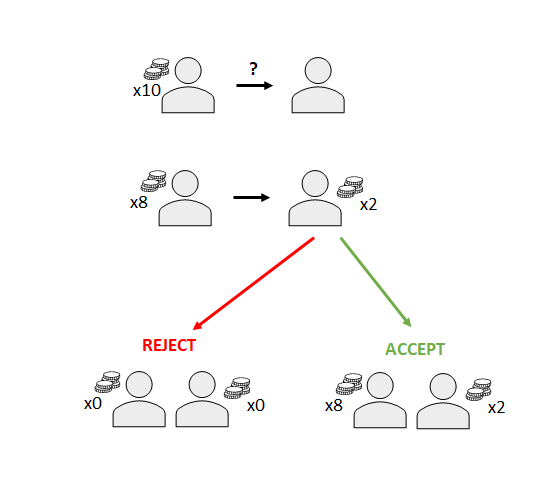

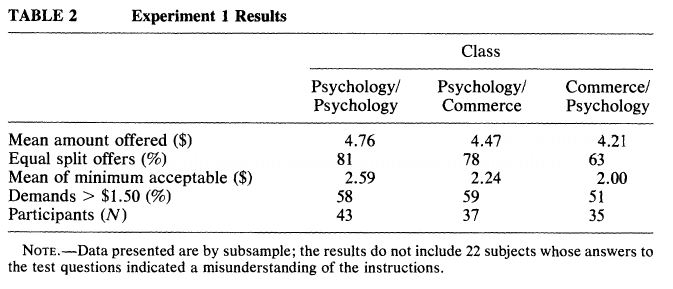

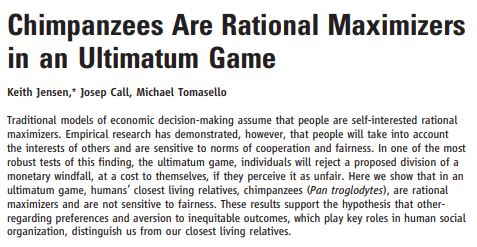

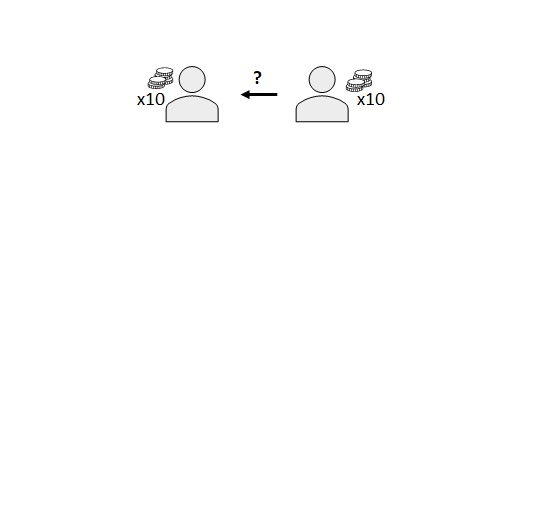

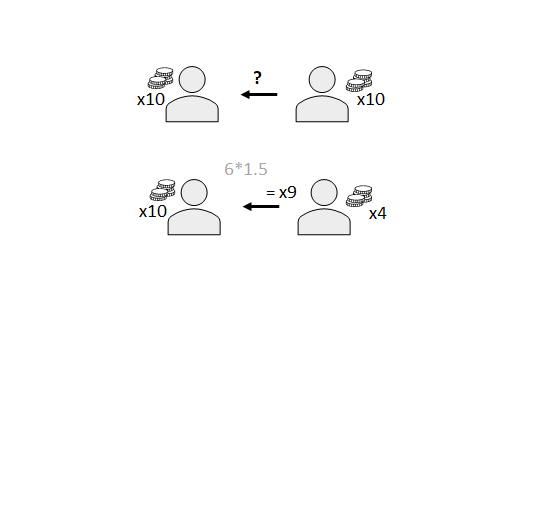

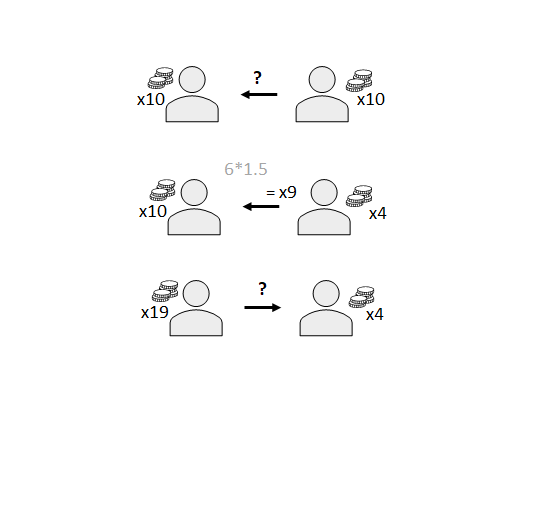

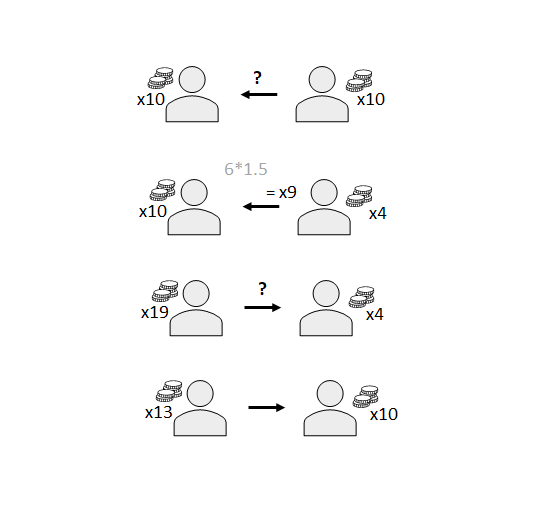

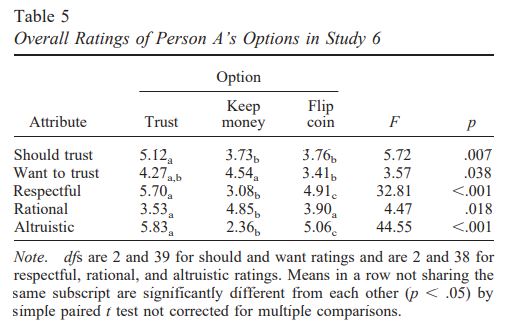

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Social dilemma games ## Week 5 - Moral Psychology --- # Week 5 This week, we will be discussing moral behavior, particularly suppressing self-interest for the interests of others and the collective .highlight-blue[In week 5:] - **What can economic games tell us about how we cooperate with each other?** - **How trusting and generous are we towards strangers?** - How concerned are we about being perceived as *moral*? - Does *true* altruism exist or are all pro-social acts inherently selfish? --- # The tragedy of the commons .footnote[Hardin (1968)]  ??? Picture a pasture, one that is shared by all herders in a town. Each herder has one sheep. --- # The tragedy of the commons .footnote[Hardin (1968)]  ??? One day one herder, seeking wealth, adds one more animal to his herd. --- # The tragedy of the commons .footnote[Hardin (1968)]  ??? Seeing the herder gaining the system, another herder follows suit. --- # The tragedy of the commons .footnote[Hardin (1968)]  ??? And suddenly there are many animals grazing in the commons. --- # The tragedy of the commons .footnote[Hardin (1968)]  ??? Unfortunately, there become too many animals that the land becomes overgrazed. --- # The tragedy of the commons .footnote[Hardin (1968)]  ??? Now a barren land, no animals can live on the commons. --- # The tragedy of the commons .footnote[Hardin (1968)] - The tragedy of the commons describes what tends to occur when many people share a limited resource - When people seek to maximize their individual gains, the resource dwindles until there is none left ??? "Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all" - Hardin E.g., the environment --- # The tragedy of the commons Many psychologists theorize that morality evolved as a solution to problems like the tragedy of the commons, for people to be able to .highlight-blue[suppress selfishness] and .highlight-blue[cooperate with each other] .right-column-small[] .left-column-big[ >.smallish[Moral systems are interlocking sets of values, virtues, norms, practices, identities, institutions, technologies, and evolved psychological mechanisms that work together to suppress or regulate selfishness and *make cooperative social life possible*.] .right[-Jonathan Haidt, 2010]] --- # The tragedy of the commons Many psychologists theorize that morality evolved as a solution to problems like the tragedy of the commons, for people to be able to .highlight-blue[suppress selfishness] and .highlight-blue[cooperate with each other] .right-column-small[ ] .left-column-big[ > .small[Morality is a set of psychological adaptations that allow otherwise selfish individuals to reap the benefits of cooperation... Selfish herders will keep adding animals to their herds until the individual costs outweigh the individual benefits... Moral herders, however, may be willing to limit the sizes of their herds out of concern for others, even though such restraint imposes a net cost on oneself. ] .right[-Joshua Greene, 2013]] --- # Cooperation One way that psychologists study cooperation is through social dilemma games, where individuals are forced to decide between a selfish or cooperative action - You may have heard about some of these: - The Prisoner's dilemma - Chicken - The public goods game - The commons dilemma - The ultimatum game - The trust game - The dictator game (next class) --- # Split or steal? <center><br> <iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/9kuZjMf6J6g" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe> </center> https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9kuZjMf6J6g ??? This is a clip from the British day time show Golden Balls which aired from 2006-2008 Pause and ask the class what they think will happen --- # Split or steal? <center>  --- # The prisoner's dilemma <center>  ??? Split or steal is a version of what is called the Prisoner's dilemma In this dilemma, two people rob a bank together and are being interrogated by the police --- # The prisoner's dilemma <center>  ??? If they both keep quiet, then they will both get two years in prison --- # The prisoner's dilemma <center>  ??? However, cooperation isn't the best outcome for them. If they confess and their partner is silent, then they only get 6 months in prison --- # The prisoner's dilemma <center>  ??? But if they both confess, then they both get 8 years --- # The prisoner's dilemma .right-column-med[] - In the classic prisoner's dilemma, rewards can be ranked as follows: - Confess while other is silent > <br>Both silence (cooperate) > <br>Both confess > <br> Silent while other confesses - Players may choose to confess because: - Selfishness (they want to only be in prison for 6 months) - Risk-aversion (8 years is not as bad as 12) --- # Chicken .pull-left[<br><center>**Prisoner's dilemma**<br><br> ] .pull-right[<br><center>**Chicken**<br><br> ] --- # Chicken .right-column-med[] - In chicken version of the prisoner's dilemma, rewards can be ranked as follows: - Confess while other is silent > <br>Both silence (cooperate) > <br>Silent while other confesses > <br>Both confess - Players may choose to confess because: - Selfishness (they want to only be in prison for 6 months) - ~~Risk-aversion~~ ??? Some consider the prisoner's dilemma a better measure of selfishness because it removes the possibility that people don't cooperate because they are risk adverse --- # Tit for tat .footnote[Axelrod (1984)] Axelrod (1984) wanted to know how cooperation can occur in a competitive environment where the two players gain immediately but not in the long run from selfish actions (e.g., like one would experience in a nuclear arms war) - He invited people to come up with computer code that would win the most in a repeated version of the Prisoner's dilemma - He found that the winning strategy is *tit-for-tat* --- # Tit for tat .footnote[Axelrod (1984)] .pull-left[- *Tit-for-tat* works like this: - Cooperate on the first round - In subsequent rounds, copy your partner's move ] .pull-right[ |Round| TFT player | Player 2| |:--:|:----:| :----:| |1|C|C| |2|C|C| |3|C|D| |4|D|D| |5|D|C| |6|C|C| |7|C|C| ] --- # Tit for tat .footnote[Axelrod (1984)] .pull-left[- *Tit-for-tat* works like this: - Cooperate on the first round - In subsequent rounds, copy your partner's move .dq-c[Why do you think <br> this strategy is successful?] ] .pull-right[ |Round| TFT player | Player 2| |:--:|:----:| :----:| |1|C|C| |2|C|C| |3|C|D| |4|D|D| |5|D|C| |6|C|C| |7|C|C| ] --- # Tit for tat .footnote[Axelrod (1984)] .pull-left[ - *Tit-for-tat* is successful because - It's goal is cooperation - It's easy for the other player to figure out - It's not exploitable - It's forgiving ] .pull-right[ |Round| TFT player | Player 2| |:--:|:----:| :----:| |1|C|C| |2|C|C| |3|C|D| |4|D|D| |5|D|C| |6|C|C| |7|C|C| ] ??? Reciprocity is important. Be generous and forgiving, but also be fair/ set boundries --- # Activity **Instructions**: Get into groups of 4-6. We are going to play *three* rounds of a game called the "public goods game." To play, click [here](https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1PLquczZ0sBYNuD2zdMu4LTS_d8IyahSPedONB11MxR0/edit?usp=sharing). In the spreadsheet, navigate to your group tab, enter the number of players, and exchange "player 1", "player 2", etc. with your names. For the game, each player starts with $20. HOW TO PLAY A ROUND .smaller[ 1. At the start of the round, decide how much money you want to "invest". You can invest up to $20 in a round but you don't have to invest anything. 2. Enter the number (from 0 - 20) you want to invest in the "investment" row under your name. If you choose not to invest anything, enter "0". 3. At the end of the round, the group's investments will be added together, **doubled**, and then split equally between participants.] --- # The public goods game <center><br><br>  ??? Each player starts with $20 --- # The public goods game <center><br><br>  ??? Each player chooses how much they want to invest. Some (labeled here "C" for cooperative) with give more than others (labeled here "S" for selfish) --- # The public goods game <center><br><br>  ??? The invested money is multipled by a factor greater than 1 --- # The public goods game <center><br><br>  ??? The investment is split equally between members and returned --- # The public goods game <center><br><br>  ??? Here is the result at the end of the round. The selfish person, who barely invested any money, gained the most money, while the cooperative person ends up with the least amount --- # The public goods game <center><br><br> .pull-left[] .pull-right[] ??? Comparing the sample game to earnings if everyone refused to play --- # The public goods game <center><br><br> .pull-left[] .pull-right[] ??? Comparing the sample game to earnings if everyone was maximally cooperative. Notice that the selfish person actually made more than they would have if everyone was cooperative --- # The public goods game .footnote[Fehr & Gächter (2000)]  ??? Researchers found that in repeated rounds, people tend to give less and less to the pile. This is because people see that free-riders are getting more money than them and they think that is unfair --- # Altrustic punishment .footnote[Fehr & Gächter (2000)] #### Method - Researchers gave people the opportunity to punish "free-riders" - They called this punishment "altruistic" because in order to punish someone (get their earnings taken away), you would need to spend your own money --- # Altrustic punishment .footnote[Fehr & Gächter (2000)] .right-column-med[] .left-columng-med[ #### Results - In 10 rounds, they found that 84.3% of participants punished at least once and 9.3% punished at least 10 times - Most punishment was from cooperators to defectors (74.2%) - The strongest cooperators punished the most] ??? Explanation of figure: people who were getting the least money from the investment (because they were cooperating a lot) gave the heaviest punishments --- # Altruistic punishment .footnote[Fehr & Gächter (2000)]  ??? When people we able to punish, they group did better overall --- # The commons dilemma <center><br><br>  ??? The commons dilemma tests a tragedy of the commons situation. There is a finite number of resources. The resources will be replenished, so people need to take the money slowly. If anyone takes too much, then no one gets any money --- # The commons dilemma <center><br><br>  --- # The commons dilemma <center><br><br>  --- # The commons dilemma <center><br><br>  --- # The ultimatum game <center>  ??? In the ultimatum game, player A is give an amount of money. They get to choose how much money they give to player B --- # The ultimatum game <center>  ??? Player B can either reject or accept the offer. If they accept it, then the money gets split as proposed. If its rejected, they both get $0. --- # The ultimatum game <center> .pull-left[]</center> .pull-right[.dq-c[What offer would a "rational" person accept?] .dq-c[Why wouldn't someone accept an offer?] .dq-c[What do you think the average offer is? The average accepted offer?]] --- # The ultimatum game .footnote[Kahneman, Knetsch, & Thaler (1986)] <center><br>  ??? The majority of people offer a 50-50 split They also asked people how low they would accept. mean of that number was around 2. most demanded over $1.50 to accept --- # The ultimatum game .footnote[Jensen, Call, & Tomasello (2007)] <center><br><br>  --- # The trust game <center>  ??? In the trust game, player B has an endowment of $10 too. They get to decide how much money to give to player A --- # The trust game <center>  ??? When player B gives it to player A, the money gets multiplied by a factor greater than 1 --- # The trust game <center>  ??? But now that player A has player A's money, they can decide how much money to give back to player B --- # The trust game <center>  --- # The trust game .footnote[Dunning et al. (2014)] #### Method (study 1) - Researchers had participants play a version of the trust game where participants could give $5 to a stranger with the chance that it would quadruple to $20 --- # The trust game .footnote[Dunning et al. (2014)] #### Results (study 1) - About 52.5% of people believed that they would get some money back - However, 71% of people gave some money to the stranger - Behavior was driven by *injunctive norms*, or perceptions about what one should do or should not do in the situation --- # The trust game .footnote[Dunning et al. (2014)] #### Method (study 6) Participants could choose from the following: - Keep the $5 - Trust another person to split or keep the $5 - Let the other person flip a coin, which will determine if they keep or split the $5 --- # The trust game .footnote[Dunning et al. (2014)] #### Results (study 6) Participants chose to: - Keep the $5 **(24%)** - Trust another person to split or keep the $5 **(54%)** - Let the other person flip a coin, which will determine if they keep or split the $5 **(22%)** Participants overwhelmingly chose to share the money over keeping it They chose to trust the stranger over leaving it to chance --- # The trust game .footnote[Dunning et al. (2014)] .pull-right[] .pull-left[#### Results (study 6) Participants indicated that they believed that they *should* choose to trust, even though they wanted to trust and to take the money equally (see Table) - These findings suggest that people trust because they feel obligated to, not because they want to ] --- # Summary - Morality may have evolved because it allowed individuals to work together for mutually beneficial outcomes - Cooperative behavior can be studied in a lab with economic games - From economic games, we have learned that participants are much more generous and trusting of strangers than is "rational" - Cooperation is most successful when players give fair offers and reciprocate when relevant - People are willing to sacrifice their own earnings to punish free loaders - Generosity may be driven by what participants think they ought to do, rather than what they actually want to do .highlight-blue[Next class]: altruism and the moral reputation