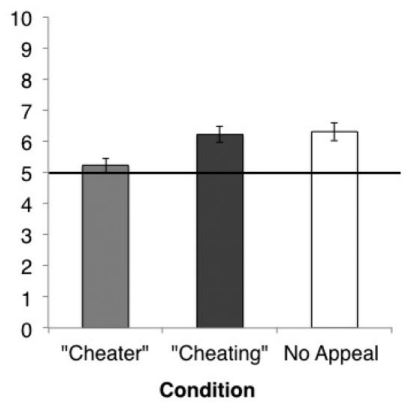

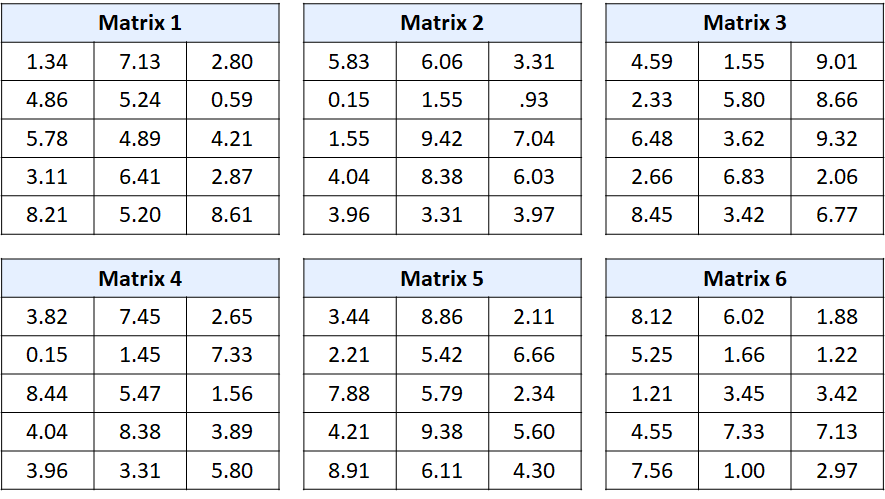

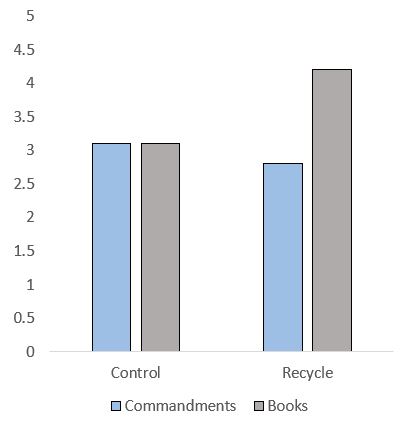

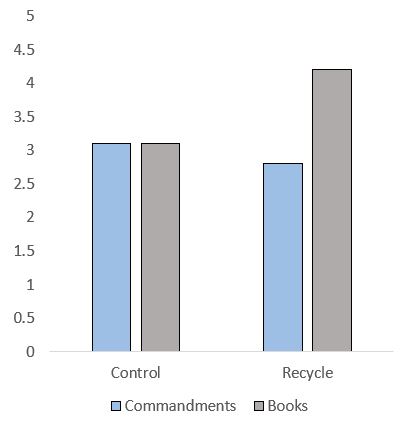

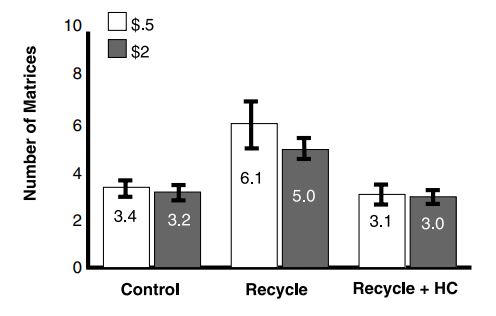

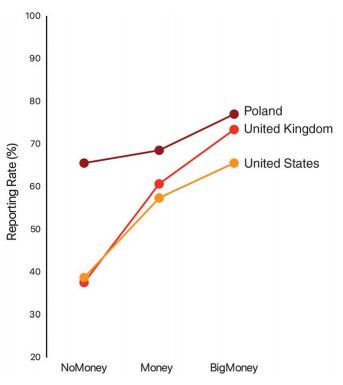

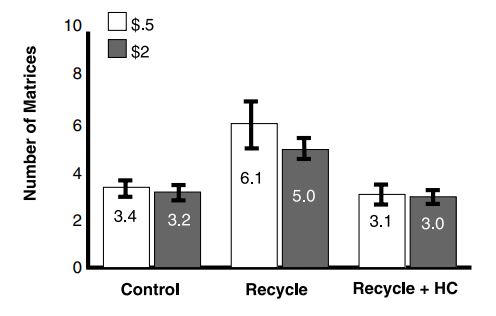

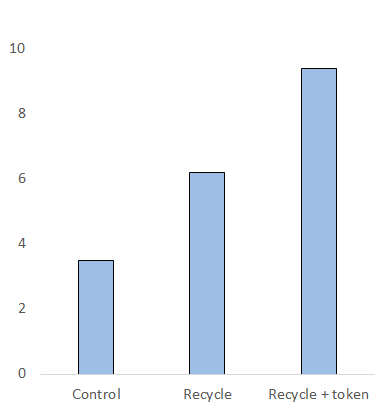

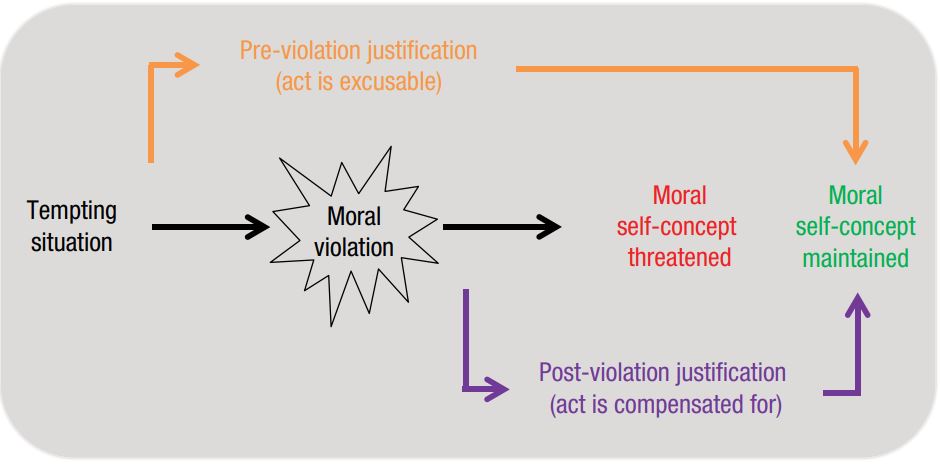

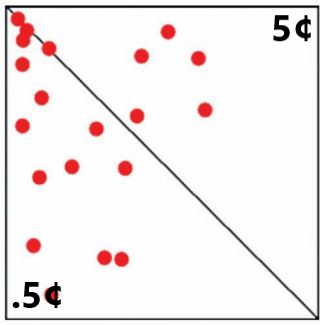

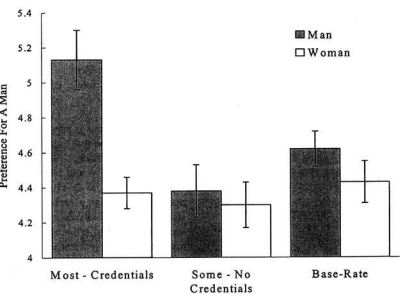

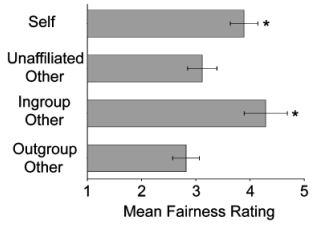

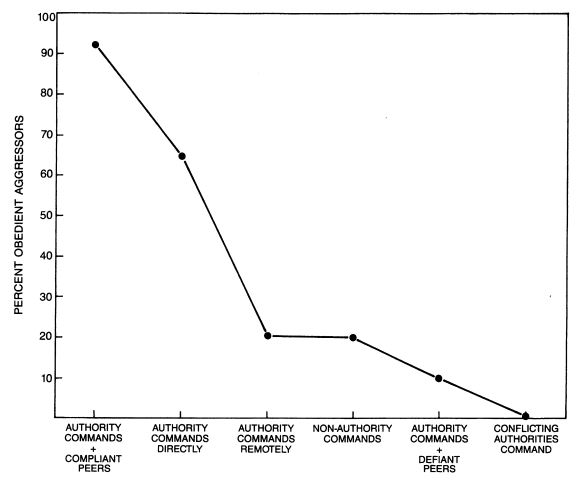

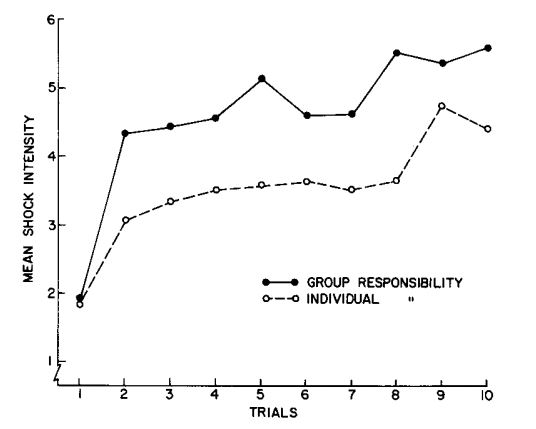

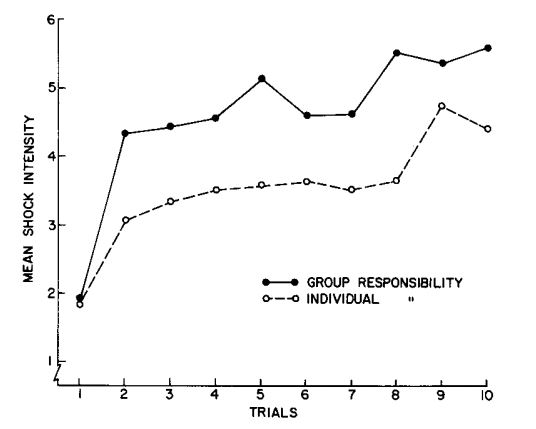

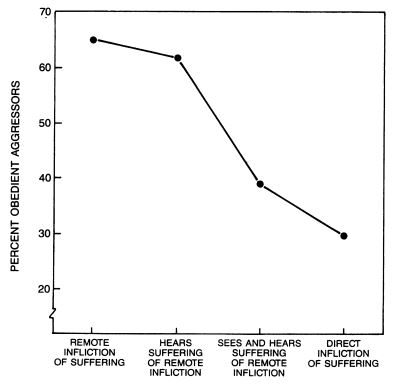

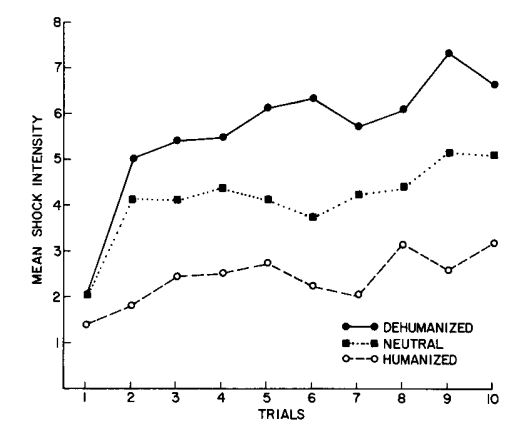

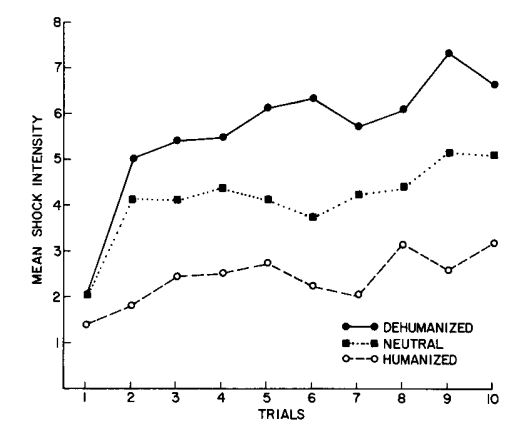

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Self-concept maintenance ## Week 7 - Moral Psychology --- # Week 7 This week, we will be discussing the moral self. .highlight-blue[In week 7:] - How central is morality to one's self-concept? - What is a *moral identity* and how to we measure it? - **How do we maintain that we are a good person, even when we violate our own moral standards?** --- # Activity Think of a number between 1 and 5. I will give extra credit to anyone who is thinking the same number as me. Write down your guess and name on a piece of paper so that I can later assign extra credit. Please don't cheat by going to the website and looking at the next slide. --- # Activity The number I was thinking of was 2. --- #Activity .pull-left[Option 1: I will give extra credit to anyone who is thinking the same number as me. .highlight-blue[Please don't cheat] by going to the website and looking at the next slide. ] .pull-right[Option 2: I will give extra credit to anyone who is thinking the same number as me. .highlight-blue[Please don't be a cheater] by going to the website and looking at the next slide. ] .dq[.smaller[Which of these warnings do you think would most defer a person from cheating, and why?]] --- # The moral self .footnote[Bryan, Adams, & Monin (2013)] ####Method - Researchers asked for volunteers for a study about psychokinesis - Participants flipped a coin 10 times, and were asked to try to influence the outcome "with their minds" - They would receive $1 for every flip that landed on heads --- # The moral self .footnote[Bryan, Adams, & Monin (2013)] ####Method Participants were randomly assigned to receive one of two versions of a warning or to recieve no warning at all (the control condition): - **NOTE**: Please don’t [cheat/be a cheater] and report that one or more of your coin flips landed heads when it really landed tails! Even a small [amount of cheating/number of cheaters] would undermine the study, making it appear that psychokinesis is real. --- # The moral self .footnote[Bryan, Adams, & Monin (2013)] .pull-left[ ####Results - Participants claimed significantly less money (indicating less cheating) when they read "please don't be a cheater" than when they read "please don't cheat" - "Please don't cheat" did not significantly reduce cheating from no warning at all ] .pull-right[ ] --- # The moral self .footnote[Bryan, Adams, & Monin (2013)] ####Discussion - Most people are highly motivated to maintain a positive self-concept, to think of ourselves as *good* - An individual can cheat a little amount without it threatening their self-concept but will refrain from cheating when it does threaten their self-concept -- .dq[.smaller[Should we apply this everywhere, e.g., "please don't be a litterer," "please don't be a drunk driver"?]] ??? or do you foresee any negative consequences of this style of behavior change? E.g., it's not clear what effect it will have on one's identity. Will many come to see themselves as a cheater and their behavior increase? --- # Self-concept maintenance .footnote[Mazar, Amir, & Ariely (2008)] **Self-concept maintenance theory** of dishonest behavior states that individuals are torn between benefiting from cheating and maintaining a positive self-concept .pull-right[] .pull-left[People are able to compromise by cheating a little, but only enough so that it does not threaten their positive self-concept] ??? E.g., everyone has a number in which they are comfortable going over the speed limit without feeling like a reckless person. Can ask class what their number is. --- # Self-concept maintenance .footnote[Mazar, Amir, & Ariely (2008)] - Mazar, Amir, & Ariely (2008) propose two mechanisms that allow a person to balance cheating with their positive self-concept - **Attention to standards**: When people are not attending to their moral standards, they are less likely to follow them ??? You can remind them of moral rules by having them recite the 10 commandments, for example (like in the last lecture) --- # Self-concept maintenance .footnote[Mazar, Amir, & Ariely (2008)] - Mazar, Amir, & Ariely (2008) propose two mechanisms that allow a person to balance cheating with their positive self-concept - **Attention to standards**: When people are not attending to their moral standards, they are less likely to follow them - **Categorization:** An individual can categorize their action in different terms in order to justify it ??? Stealing pencils vs. money from work, or stealing tokens vs. money (experiment we talked about in dishonesty lecture). Would you steal money out of a college dorm vs. some milk? --- # Self-concept maintenance .footnote[Mazar, Amir, & Ariely (2008)]  ??? Reminder of the matrix task --- # Attention to standards .footnote[Mazar, Amir, & Ariely (2008)] #### Method (study 1) - Participants were given 20 matrices to solve in 4 minutes - They were told that two people would be randomly selected at the end of the experiment to earn $10 for every solved matrix -- - Random assignment to two conditions - **Recycle condition** OR **control** (hand to experimenter) - **10 commandments condition** OR **Control** (list 10 books you read in high school) --- # Attention to standards .footnote[Mazar, Amir, & Ariely (2008)] .pull-left[#### Results (study 1) - In the control condition (not able to cheat), participants completed about 3 matrices on average - In the recycle condition, participants cheated after reciting books they read in high school but not after reciting the commandments] .pull-right[] --- # Attention to standards .footnote[Mazar, Amir, & Ariely (2008)] .pull-left[#### Discussion (study 1) - Individuals are less likely to cheat when they are reminded of their moral values - People only cheated about 1-2 matrices on average (they could have solved up to 20 matrices) ] .pull-right[] --- # Attention to standards .footnote[Mazar, Amir, & Ariely (2008)] .pull-left[####Discussion (study 1) - There was an insignificant correlation between number of commandments that a person could recall and their matrix score in the recycle condition .dq-c[.smaller[What does this say about religiosity?]]] .pull-right[] --- # Attention to standards .footnote[Mazar, Amir, & Ariely (2008)] #### Method (study 2) - Participants were given 20 matrices to solve in 4 minutes - Participants were randomly assigned to one of the six combinations: - **50 cents** per matrix or **$2** per matrix - **Control** or **Recycle** or **Recycle + honor code** --- # Attention to standards .footnote[Mazar, Amir, & Ariely (2008)] .pull-left[#### Results (study 2) - In the recycle condition, people claimed about two more matrices when they did not see an honor code - The money manipulation was not significant, although this may be because $.50 is not different enough from $2] .pull-right[ ] ??? (see Wallet study from Altruism lecture) --- # Attention to standards .footnote[Cohn et al. (2019)] .right-column-med[ ] .left-column-med[ #### The missing wallet study - When a "big money" condition ($94.15) was added, people were even more likely to return the wallet .dq-c[How does this finding support self-concept maintenance theory?] ] --- # Attention to standards .footnote[Mazar, Amir, & Ariely (2008)] .pull-left[#### Discussion (study 2) - Individuals are less likely to cheat when they are reminded of their moral values - Interestingly, the institutions that these studies were conducted at did not have an honor code at the time of the study ] .pull-right[ ] --- # Categorization .footnote[Mazar, Amir, & Ariely (2008)] #### Method (study 3) - Participants were given 20 matrices to solve in 5 minutes - They were also given $10 in an envelope and told that for every matrix that they solved, they would get 50 cents from the their money supply --- # Categorization .footnote[Mazar, Amir, & Ariely (2008)] - Participants were randomly assigned to one of the following conditions: - **Control condition** - **Recycle condition** - **Recycle + token condition:** after the participant recycled their matrix worksheet, they told the experimenter their score and the participant gave them tokens, to later exchange for real money --- # Categorization .footnote[Mazar, Amir, & Ariely (2008)] .pull-left[ #### Results & discussion (study 3) - There was a significant difference between all three groups - This suggests that the addition of token payments increased cheating ] .pull-right[] --- # Self-serving justifications .footnote[Shalvi et al. (2015)] - A **self-serving justification** is a reason that one provides to attempt to make their unethical behavior less unethical - Shalvi et al. (2015) theorize that there are two pathways in which we can avoid a threatened self-concept when we violate a moral norm (pre- and post-violation) .smallish-centered-picture[] --- # Self-serving justifications .footnote[Shalvi et al. (2015)] **Pre-violation justifications** provide justification to do the act, mainly by making the act a "gray area" where the act is acceptable **Post-violation justifications** make someone feel that they have atoned for the wrong-doing --- # Pre-violation justifications .footnote[Shalvi et al. (2015); Shalvi et al. (2011); Kouchaki & Smith (2014)] .pull-left[ #### Ambiguity When a situation is ambiguous, people are more likely to act dishonestly - Visual perception task (pictured right) - Dice task] .pull-right[ .smaller-picture[]] ??? --- # Pre-violation justifications .footnote[Shalvi et al. (2015); Shalvi et al. (2011); Kouchaki & Smith (2014)] .left-column-big[**Visual perception task** - people are more likely to choose the 5 cent side when it is more ambiguous than when it is clearly on the other side **Dice task** - participants are asked to roll a dice one or three times. For both, the first roll determines your pay (higher numbers better). The participants who rolled 3 times reported a higher number because they had rolled the higher number at some point ] .right-column-small[ ] ??? which is a smaller lie than when they hadn't rolled the number at all --- # Pre-violation justifications .footnote[Shalvi et al. (2015); Conrads et al. (2013)] .left-column-big[ #### Self-serving altruism Dishonest behavior is seen as more justifiable when it benefits both you and another person - In the dice task, people were more likely to cheat at the task when cheating would benefit oneself and one's group members ] .right-column-small[  ] --- # Pre-violation justifications .footnote[Shalvi et al. (2015); Monin & Miller (2001)] .pull-left[ #### Moral licensing When an individual justifies their dishonest behavior by considering their recent pro-social behaviors - The feeling that you have gained "moral credentials" that roll over to a new situation ] .pull-right[ ] --- # .smaller[Post-violation justifications] .footnote[Shalvi et al. (2015)] #### Cleansing Physically or mentally "cleansing" oneself after an immoral action - e.g., fasting as a religious practice ??? Empirically, this has been difficult to replicate --- # .smaller[Post-violation justifications] .footnote[Shalvi et al. (2015)] #### Confessing Confessing that you have done something unethical .dq[What do you think people prefer to give: partial or full confessions? Why?] --- # .smaller[Post-violation justifications] .footnote[Shalvi et al. (2015)] #### Distancing Comparing ones dishonest behavior to actions that are even more unethical - We tend towards hypocrisy; we judge our own behavior with different standards than the behavior of others --- # The moral hypocrite .footnote[Valdesolo & DeSteno (2007)] #### Method Participants were randomly assigned to a condition. - **Self**: Participants had to choose between allowing the program to randomly assign you and another participant to an assignment or to choose your assignment. One assignment was 10 minutes and the other was 45 minutes long. The fair thing to do would be to let the computer randomly assign you but nearly all people chose instead to do the 10 minute task. Participants then rated how fairly they had acted. --- # The moral hypocrite .footnote[Valdesolo & DeSteno (2007)] #### Method Participants were randomly assigned to a condition. - **Unaffiliated other**: Participants judged how fairly someone acted when they chose to do the 10 min task instead of being fair and randomly assigning - **Ingroup/outgroup other**: Condition 2 but with a ingroup/ outgroup member based on the minimal group paradigm (over estimators/ under-estimators) --- # The moral hypocrite .footnote[Valdesolo & DeSteno (2007)] .left-column-med[#### Results - Participants who acted unfairly rated themselves as being more fair than strangers rated the act - This hypocrisy extended to members of their ingroup ] .right-column-med[ ] --- # Moral disengagement .footnote[Bandura (1999)] .smaller[Bandura et al. (1996) created a model for how people are able to violate their moral standards when the situation necessitates it (e.g., a soldier at war) - These eight mechanisms allow one to act against one's moral standards without changing one's positive self-concept or one's moral standards] .smaller-picture[ ] ??? A lot of the early moral psychology research was motivated by WWII and the Holocaust. How could this *happen*? --- # Moral disengagement .footnote[Bandura (1999)] .pull-left[ #### Moral justification The act is made acceptable by justifying it as serving some social or moral purpose - E.g., torture a serial killer to find out where he buried the bodies ] .pull-right[<br>  .dq-c[Name another example of moral justification.]] ??? Usually utilitarian ends justify the means thinking --- # Moral disengagement .footnote[Bandura (1999)] .pull-left[ ####Palliative comparison The act is made acceptable by comparing it to an even more reprehensible act - E.g., bomb a city to stop a war (killing a city full of civilians vs. endless war) ] .pull-right[<br>  .dq-c[Name another example of palliative comparison.]] ??? Bin Laden comparing 9/11 to Japan automic bombing --- # Moral disengagement .footnote[Bandura (1999)] .pull-left[ ####Euphemistic language A reprehensible act is made acceptable by the language used - E.g., "he was arrested for having sex with an underage girl" ] .pull-right[<br>  .dq-c[.smaller[Name another example of euphemistic language.]] ] ??? Capital punishment vs. state executions --- # Moral disengagement .footnote[Bandura (1999)] .pull-left[ ####Displacement of responsibility When people view that their actions are being dictated by a higher authority - E.g., a solider is being ordered to kill civilians by their superior ] .pull-right[<br>  .dq-c[.smaller[Name another example of displacement of responsibility.]] ] --- # Moral disengagement .footnote[Bandura (1999); Milgram (1974)] .pull-left[] .pull-right[ #### Displacement of responsibility - In variations of the Milgram (1963) experiment, participants were much more likely to shock the other participant to deadly levels when the experimenter told the participants that he took full responsibility for their actions ] --- # Moral disengagement .footnote[Bandura (1999)] .pull-left[ ####Diffusion of responsibility When there are many people in a group doing an action or making a decision, no one feels entirely responsible - E.g., the board of a company makes a decision to fire 20% of their employees ] .pull-right[<br>  .dq-c[.smaller[Name another example of diffusion of responsibility.]] ] --- # Moral disengagement .footnote[Bandura, Underwood, & Fromson (1975)] .pull-left[] .pull-right[ #### Diffusion of responsibility .smaller[ - A group of three participants were told that they were assigned to supervise the decisions of three other participants - They could punish the other group for making poor decisions which shocks, and they could choose the level of shock to give] ] --- # Moral disengagement .footnote[Bandura, Underwood, & Fromson (1975)] .pull-left[] .pull-right[ #### Diffusion of responsibility .smaller[Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions - **Individual**: each supervisor was assigned to a decision maker and they were to choose the shock for their assigned decision maker - **Group**: each supervisor's shock would be averaged across the shocks so that each decision maker gets the same shock ] ] --- # Moral disengagement .footnote[Bandura (1996)] .pull-left[ ####Minimizing or ignoring the consequences .smaller[People are motivated to minimize the harm they cause to others, recalling much easier the potential benefits of their actions than the harms - E.g., a CEO much more eager to point out their positive contributions (e.g., jobs) than their negative contributions (e.g., pollution) ] ] .pull-right[<br>  .dq-c[.smaller[Name another example of minimizing or ignoring the consequences.]] ] --- # Moral disengagement .footnote[Bandura (1999); Milgram (1974)] .pull-left[ ] .pull-right[ #### Minimizing or ignoring consequences - In variations of the Milgram (1963) experiment, participants were much more likely to shock the other participant when they could not see or hear the harm and suffering that they caused ] --- # Moral disengagement .footnote[Bandura (1999)] .pull-left[ ####Dehumanization Attributing animal-like qualities to a person and removing human qualities like feelings and hopes - E.g., Nazis calling Jewish people "rats", equating them to "vermin" ] .pull-right[<br>  .dq-c[.smaller[Name another example of dehumanization.]] ] --- # Moral disengagement .footnote[Bandura, Underwood, & Fromson (1975)] .pull-left[ ] .pull-right[ ####Dehumanization .smaller[ - A group of three participants were told that they were assigned to supervise the decisions of three other participants - They could punish the other group for making poor decisions which shocks, and they could choose the level of shock to give ] ] --- # Moral disengagement .footnote[Bandura, Underwood, & Fromson (1975)] .pull-left[ ] .pull-right[ ####Dehumanization .smaller[ Randomly assignment - **Humanized**: the decision makers were described as perceptive and understanding - **Dehumanized**: the decision makers were described as animistic and rotten - **Control**: the decision makers were not described]] --- # Moral disengagement .footnote[Bandura (1999)] .pull-left[ ####Attribution of blame Attributing blame to one's adversaries, the victim, or circumstances instead of taking responsibility - E.g., Trump administration blaming the Obama administration for the family separation policy ] .pull-right[<br>  .dq-c[.smaller[Name another example of attribution of blame.]] ] --- # Summary .smaller[ - A strong motivator of moral behavior is the desire to maintain a positive self-concept - Mazar, Amir, & Ariely (2008) proposed that people can cheat without it impacting their self-concept if they fail to **attend to their standards** and if they can **re-categorize** the behavior to seem less dishonest - Shalvi et al. (2015) theorized that we use pre- and post-violation **self-serving justifications** to avoid threats to our self-concept when we violate our moral standards - Bandura (1999) proposed eight mechanisms for moral disengagement that one uses to justify the act, refuse to take responsibility, downplay the consequences, and blame the victim .highlight-blue[Due Sunday:] Nothing! Get started on the rough draft of your term paper.]